Magma Copper Company

A

perspective on a decommissioned mine

Historical Report

20200818

Back to Bill Caid's Home Page

The Experience

Back in the "stone age" I

used to work in an underground mine. Not by choice, mind

you, but the pay was too good to pass up. Being in college

at the time, money was in short supply and I already had a job

working as an EMT at a local ambulance company. Despite

requiring skills and certifications, the pay was, well,

shit. It did, however, offer the ability to work around my

class schedule, and sometimes I even got to study and/or sleep on

the job. But, lots of hours for little pay, schedule

flexibility notwithstanding.

One of the local copper mines came to the engineering college at

the University of Arizona looking for part-time employees from the

engineering student body. The pay was 3 times what I was

getting for doing manual labor. The deal was 2+ shifts a

week and because I needed the cash, I did both the ambulance and

the mine, with the inevitable impact on my physical and mental

well-being. But, at least I could buy beer. In total,

I worked there for a couple of years in two capacities. The

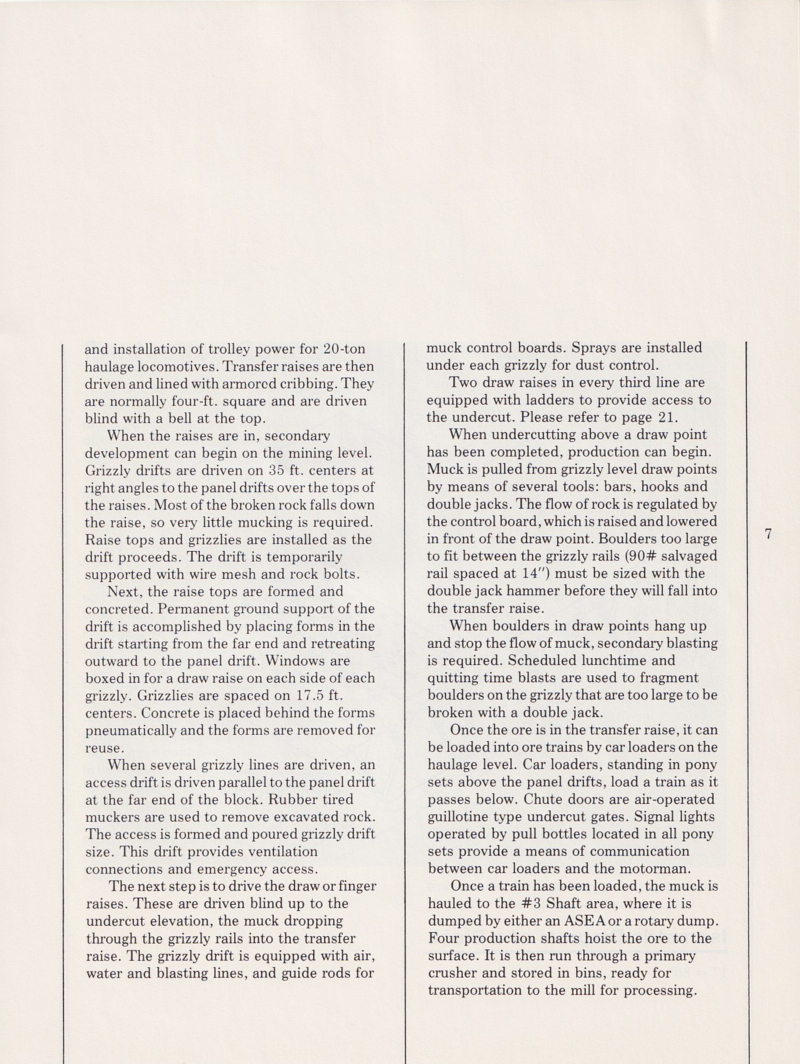

first gig was on the track maintenance crew and the second as a

production "chute tapper". Track maintenance usually

involved repairing rails that had been damaged during a derailment

and the second involved swinging a 15 lb sledge hammer known as a

"double jack". Both were hard, dirty, thankless work and

neither were fun. But it did pay well.

The mine was known to the locals as "San Manuel" for the nearby

village. Formally it was Magma Copper Company, San

Manuel Division. Unlike most of the other copper

mines in this area of southern Arizona which are "open pit", this

mine was underground, also known as a "hard-rock mine". One

of my good friends from college also worked there at the mine, as

did his father, and they obtained an informational brochure on the

mine. Those pages are scanned and included below.

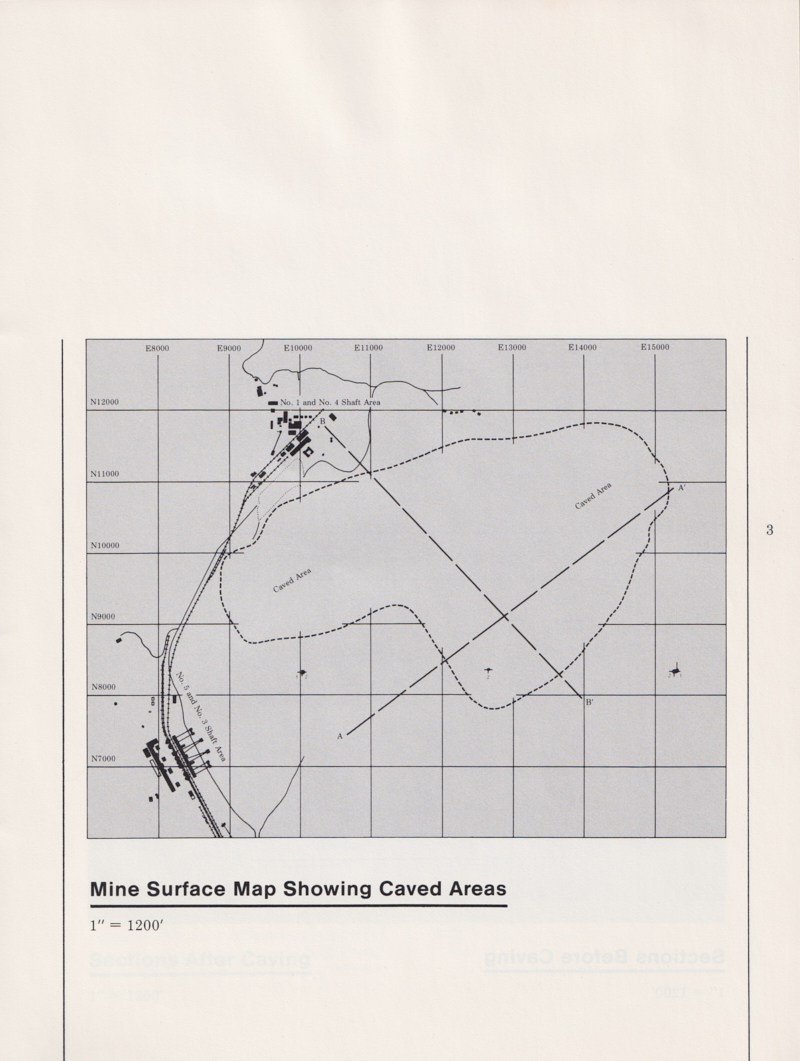

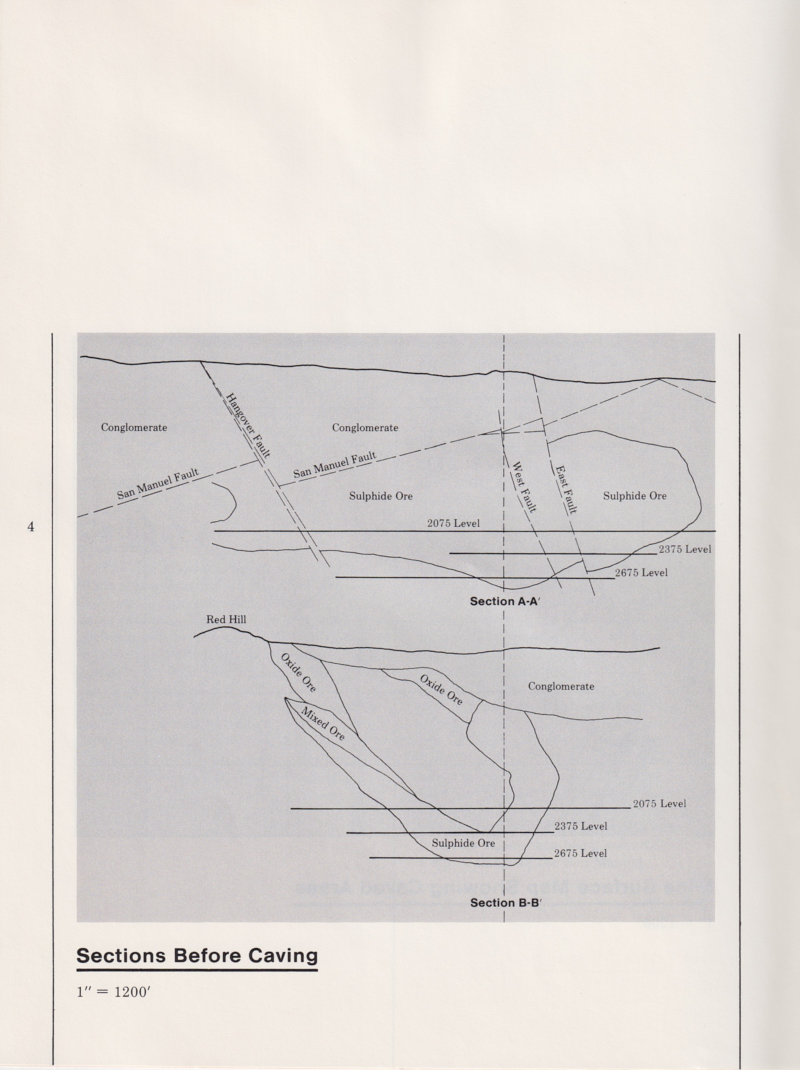

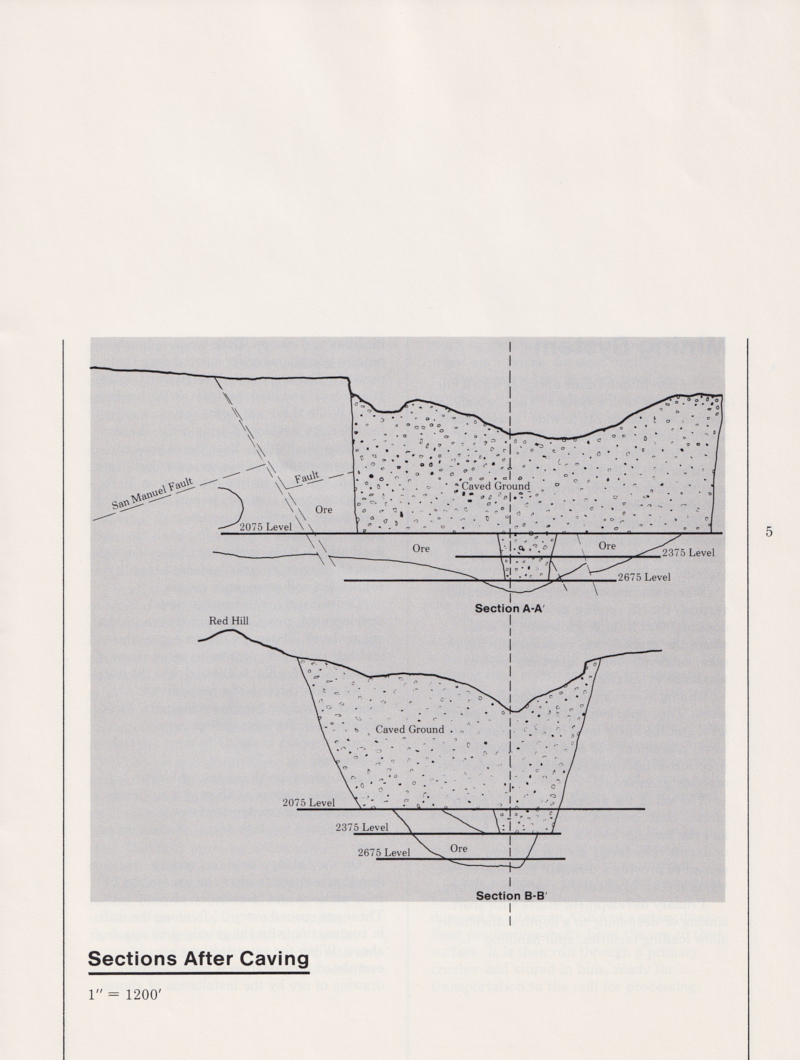

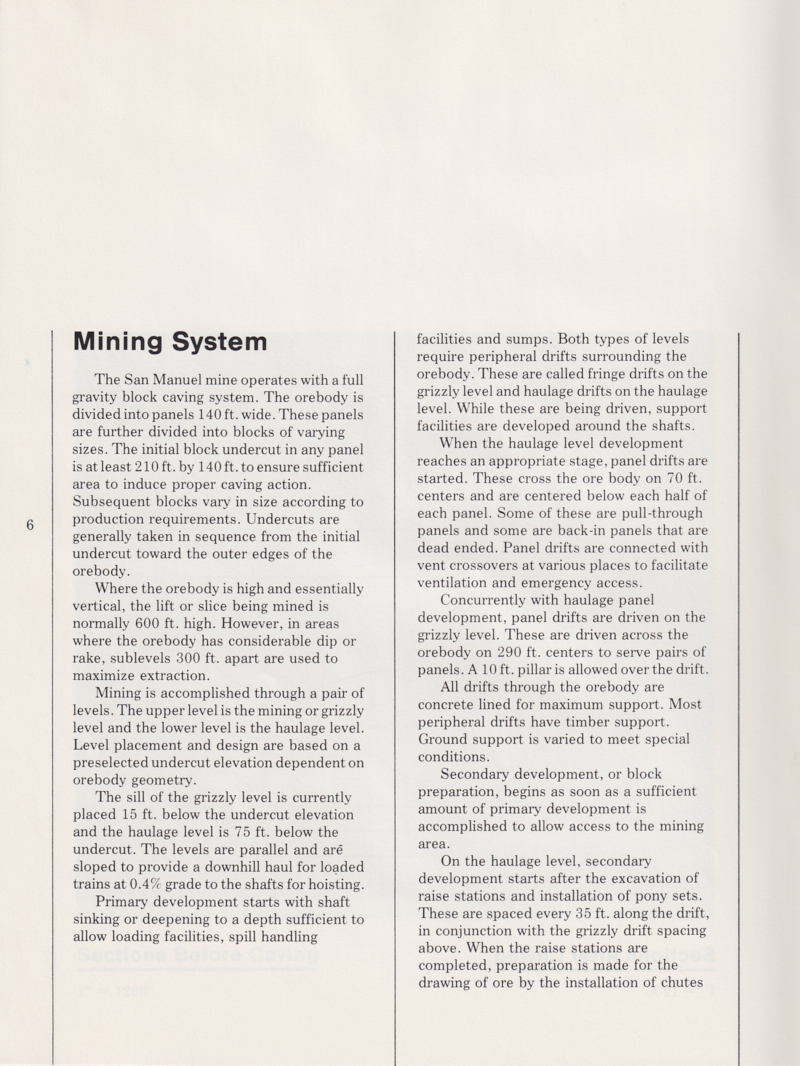

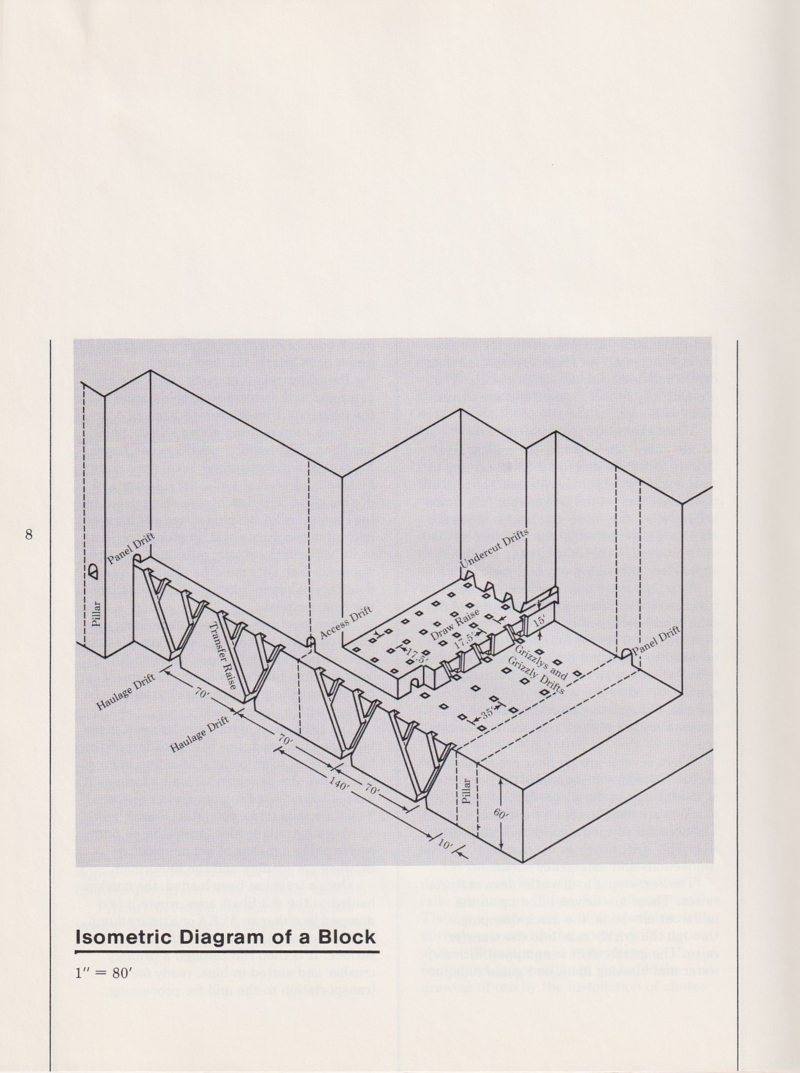

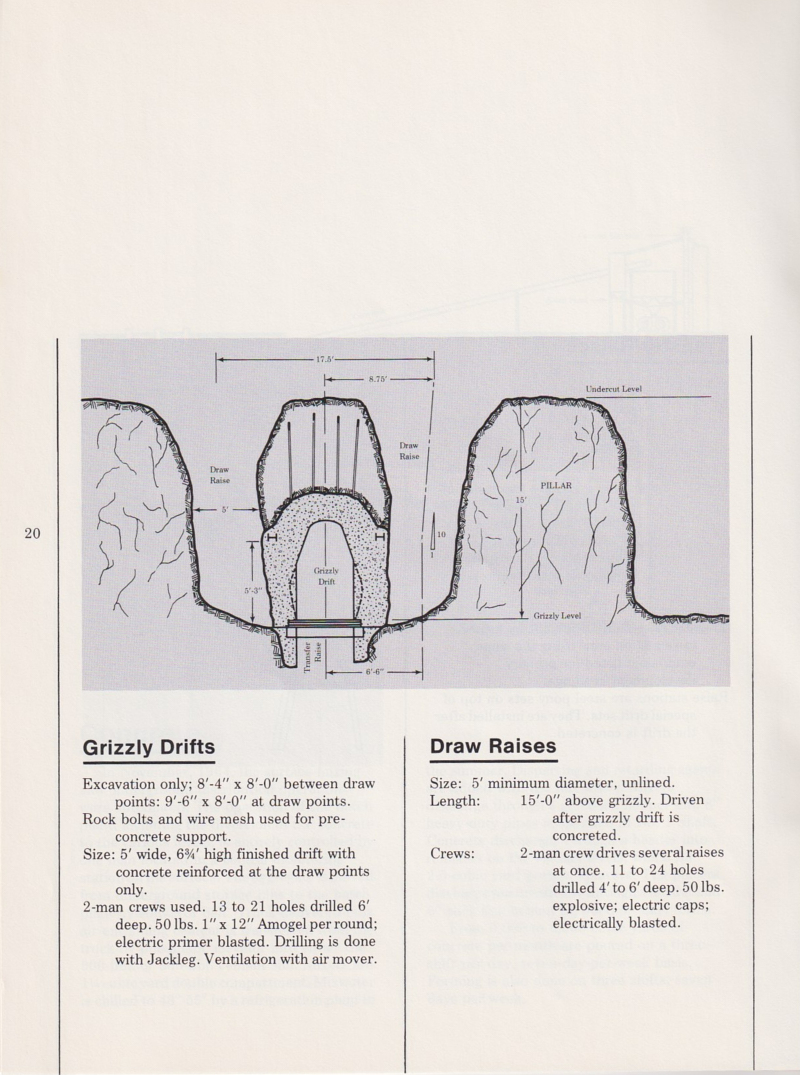

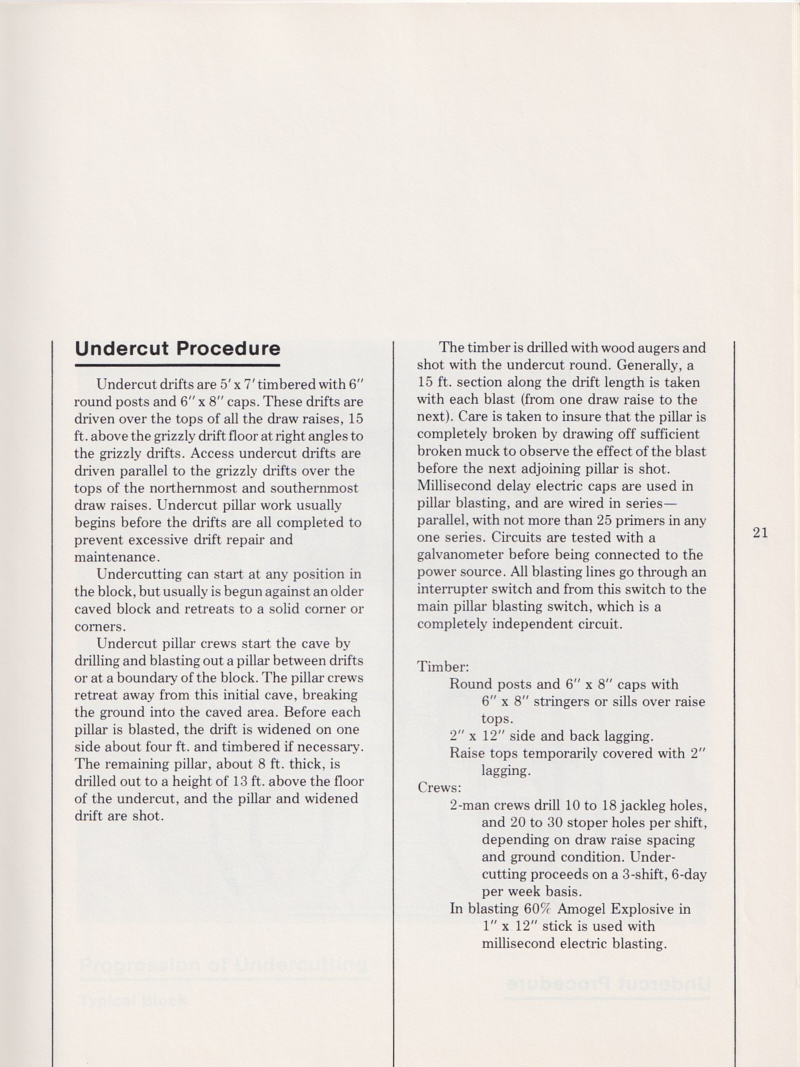

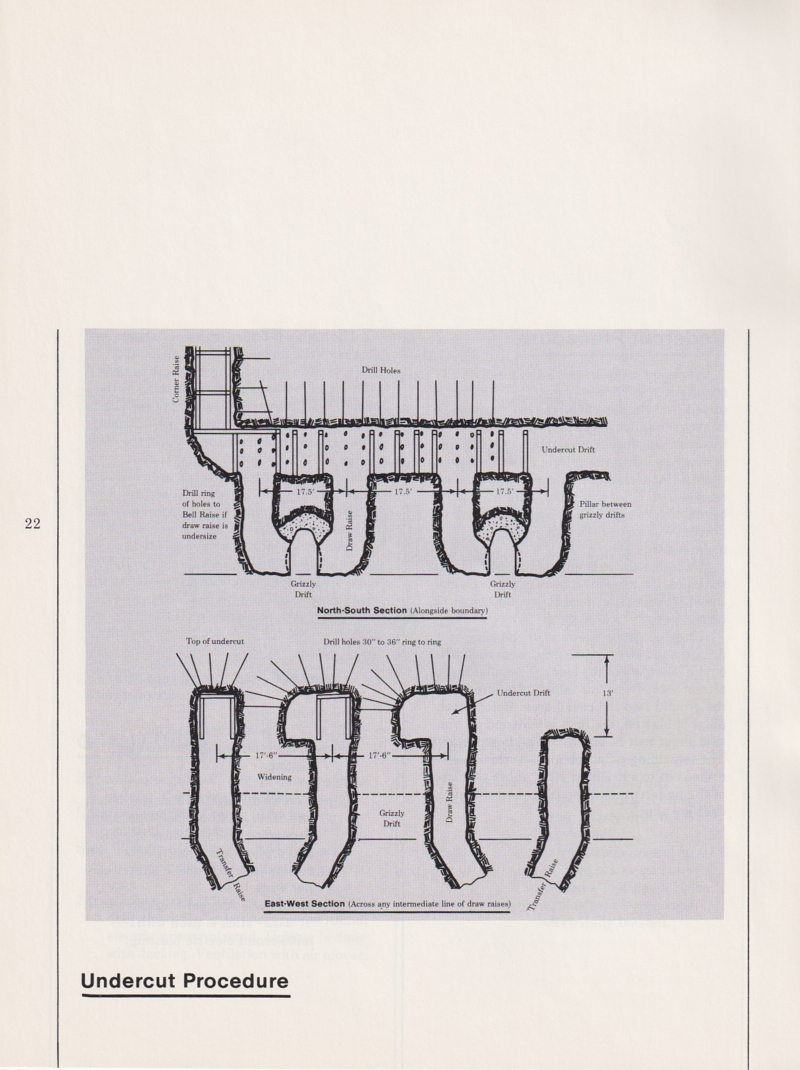

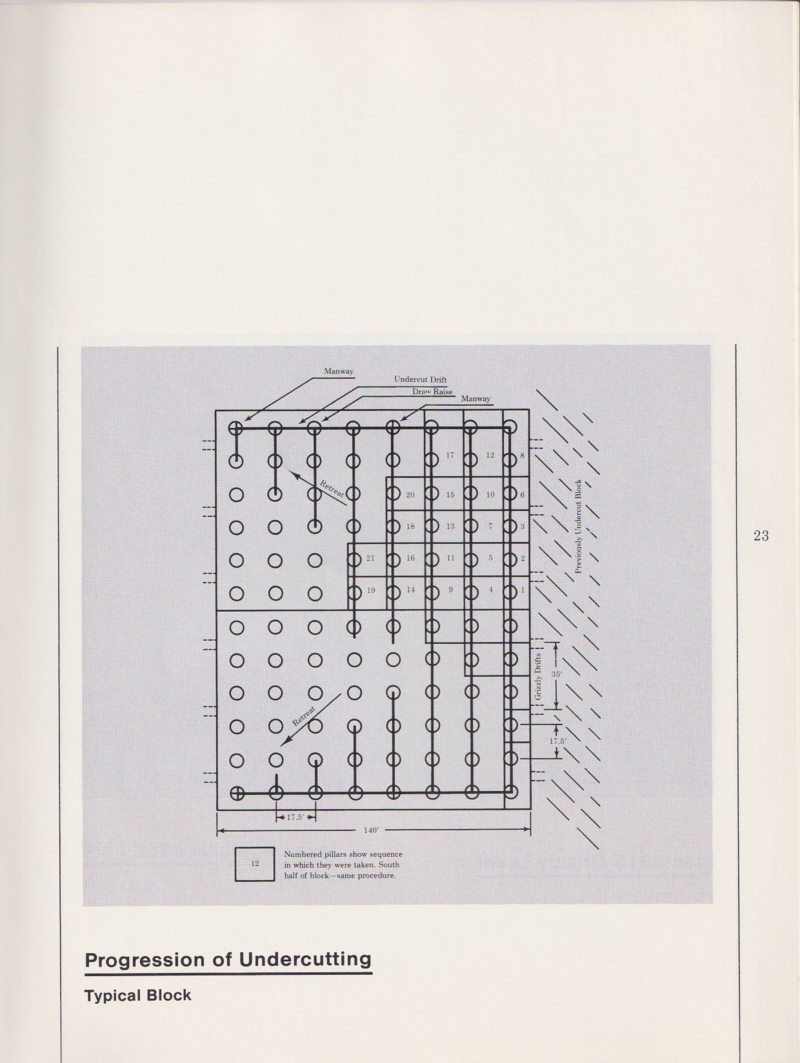

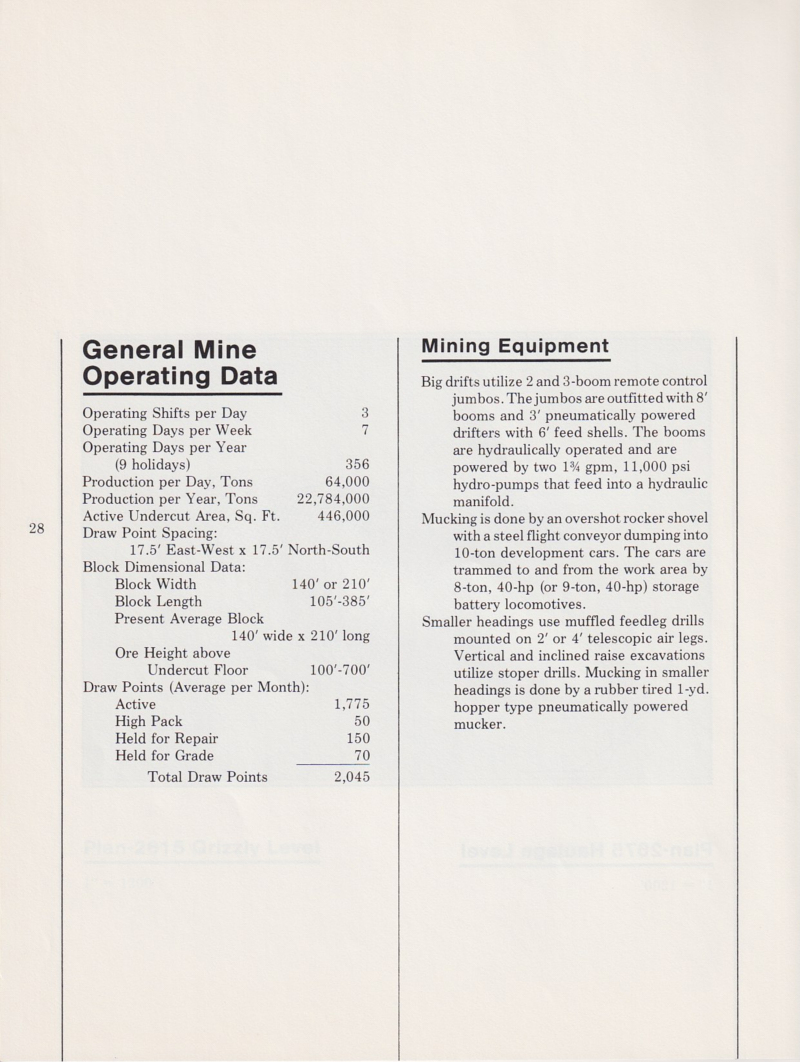

The mine used a technique called block caving where the ore body

was undercut and pulled out from below. The ground

subsequently collapsed into the hole, with cactus, trees and other

vegetation coming along for the ride. The result was a huge,

ugly scar and steep, dangerous cliffs. The mining was done

well below the local water table and without any other actions,

the mine would fill with water. During normal operations,

water was pumped from the lowest levels of the mine and discharged

at ground level. Eventually, the mining operations depleted

the ground water causing a ruckus with the local ranchers.

Mining is big business in Arizona, so you can guess how that story

ended. Magma also ran a smelter in the San Pedro river

valley a few miles from the mine. The smelter produced

plenty of sulphur-based noxious gasses which eventually killed a

large number of a sahauro cactus in the valley. In 2003

after an acquisition, the mine was permanently closed. Above

ground equipment for the mine and the smelter was sold and

eventually relocated to Chile. For

additional information on the mine, see Wikipedia. After the mine was closed, the tunnels and

shafts flooded with ground water and the site was abandoned.

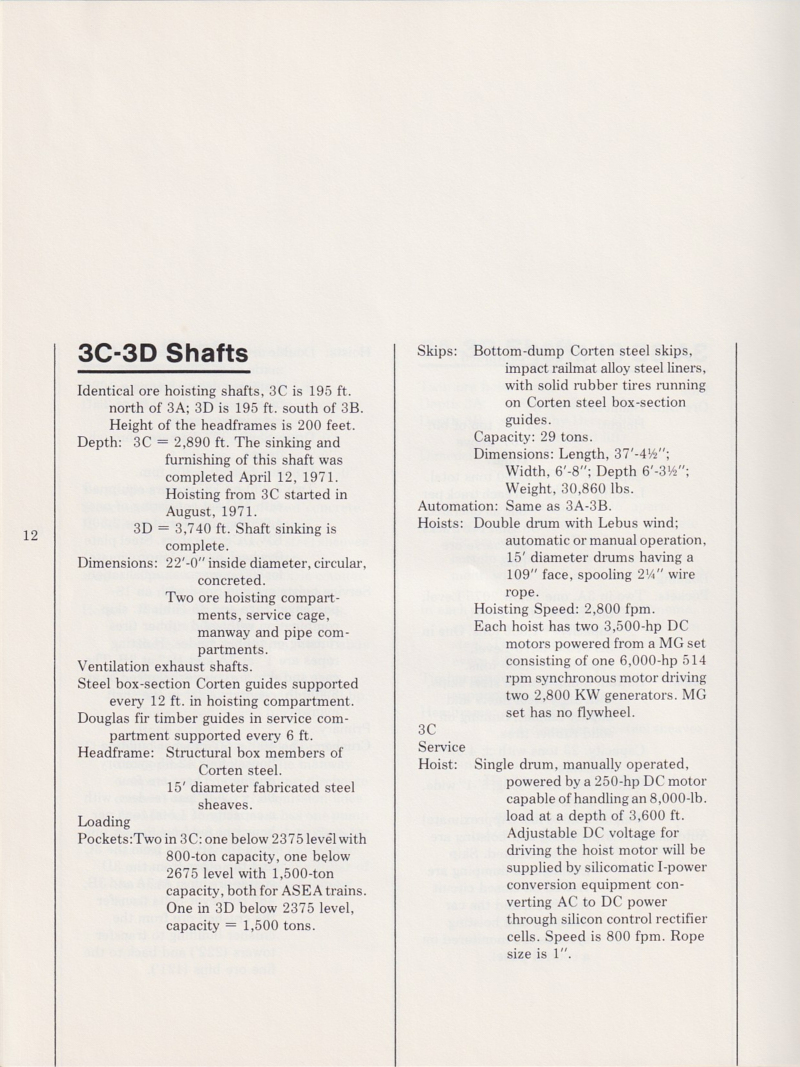

The mine had its own concrete plant for use in underground

reinforcement of the tunnels. Concrete was manufactured on

the surface and then dropped down special pipe and re-mixed at the

destination level of the mine. The concrete management

techniques are described below.

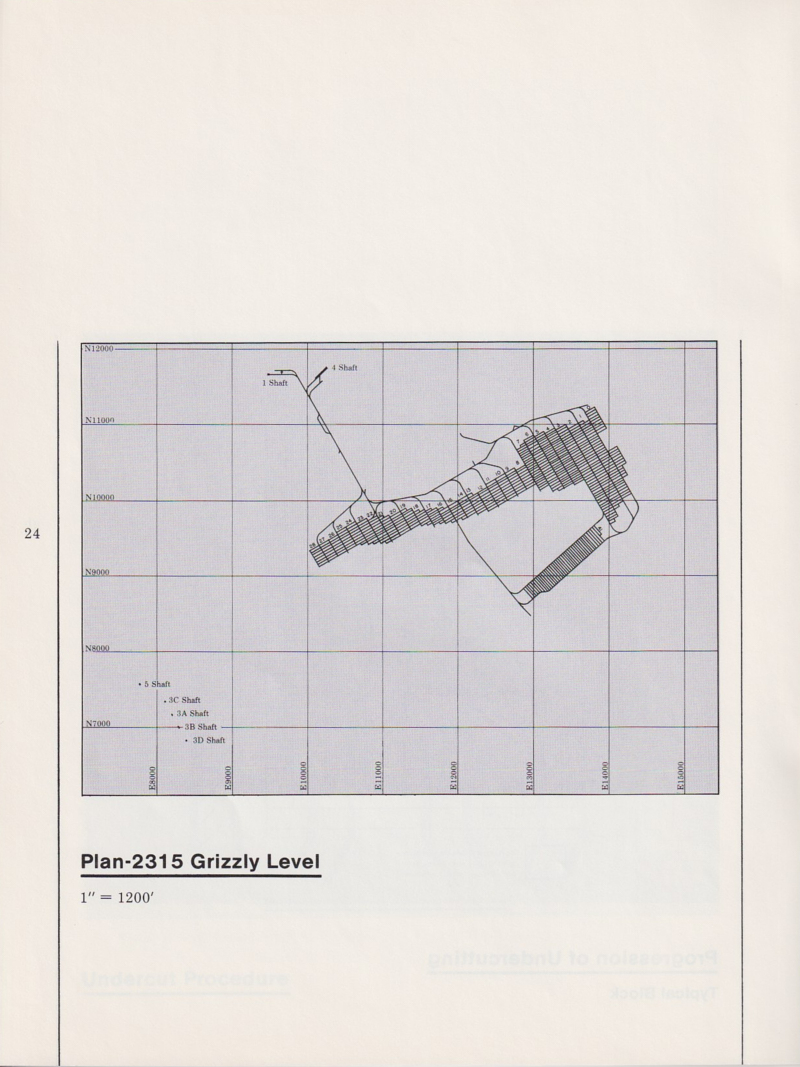

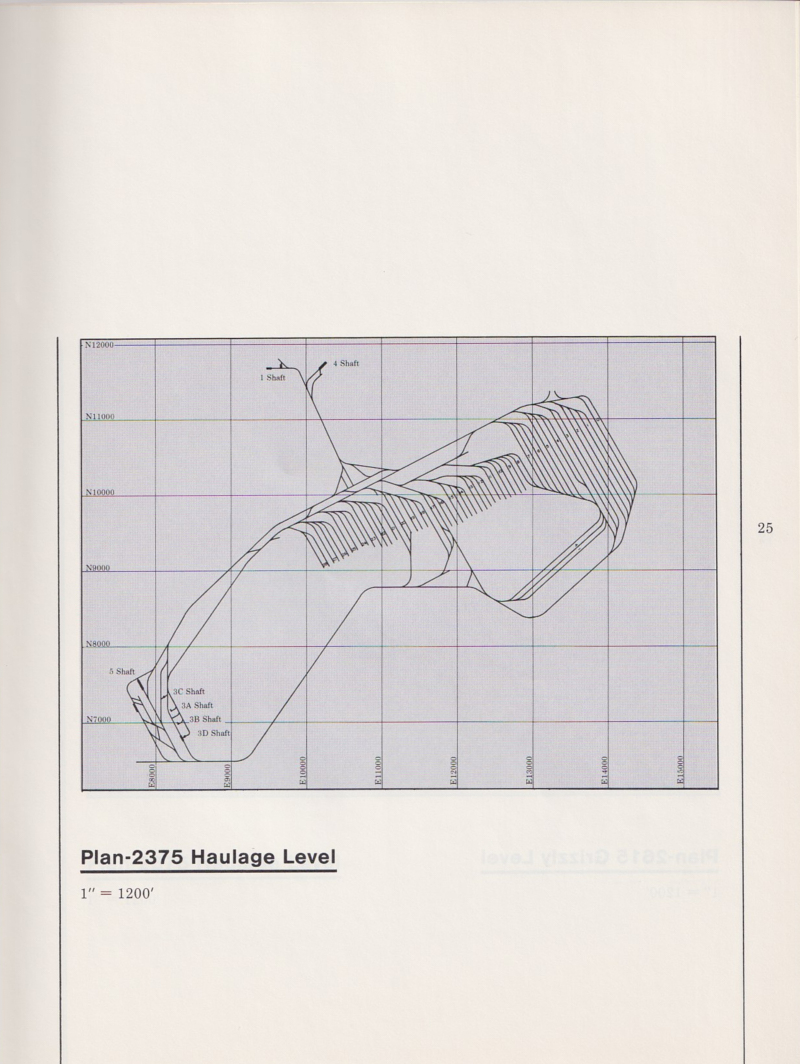

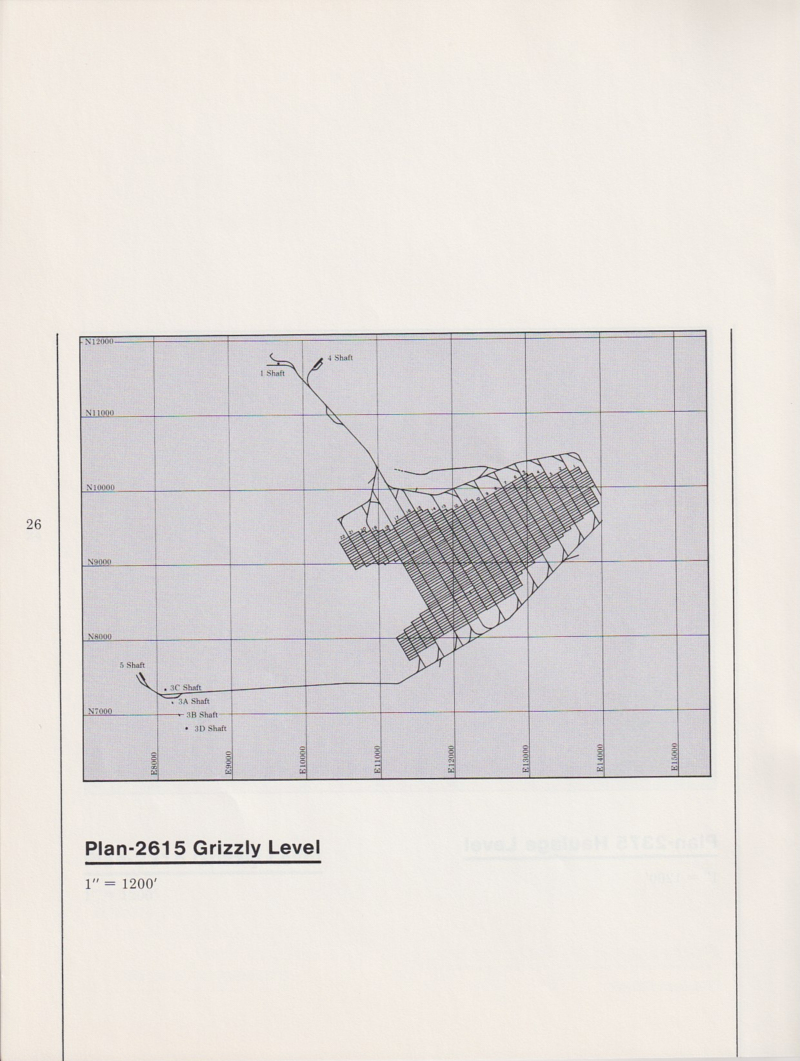

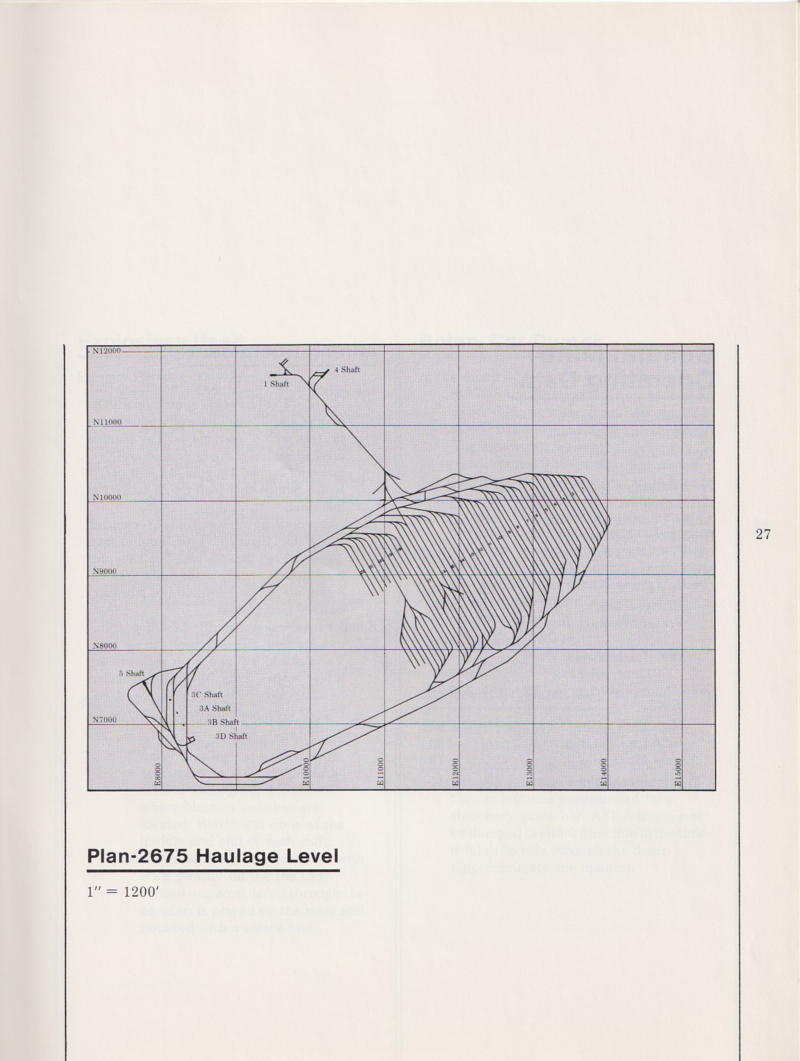

When I worked there, the mine had 6 levels: 2015 (feet below the "collar" at the surface),

2075, 2315 , 2375, 2615, and 2675. Note that to get to the

work area, you had to descend in the "cage" almost half a

mile. The deepest shaft descends to a depth of 3680

feet. I worked on each of these levels at one time or

another and the lower levels are hot-as-hell and very humid.

In the end, only about half of the available ore was

recovered. The ore body was split by a vertical fault

so the upper body was mined first. The second part was

overcome by a combination of environmental and financial issues

and remains in place today.

The photos below are

scanned from the informational brochure, complete with coffee

stains and creases. The publication date of this material

was not stated in the document. Enjoy.

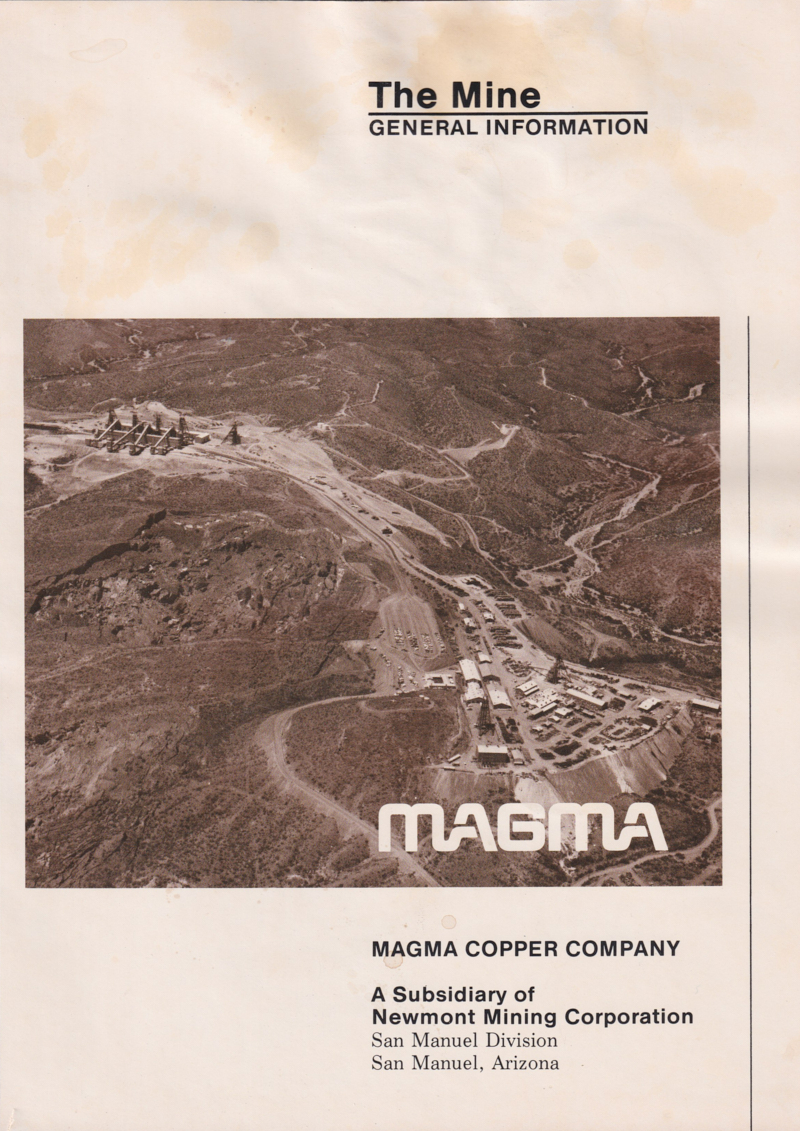

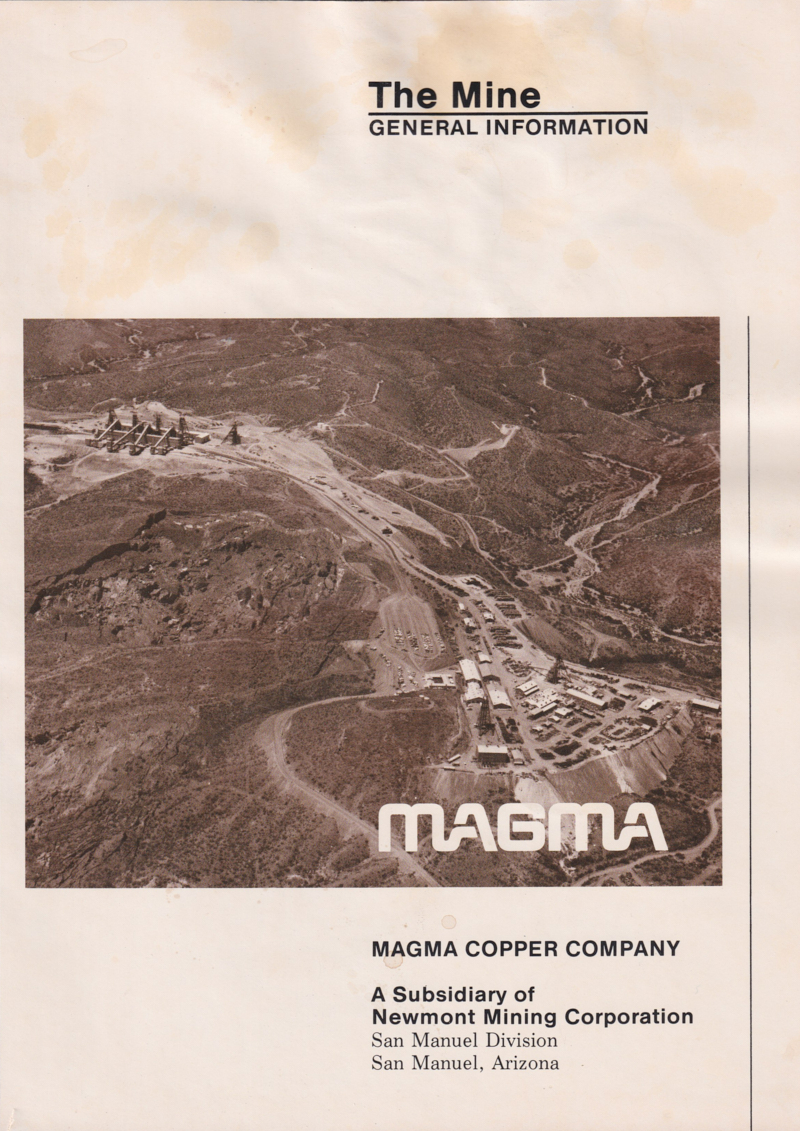

This photo must have been taken early during the mine's

operation. Note the subsidence zone in the left-of-center

area of the photo above. The production headframes used to

hoist ore-bearing muck to the surface are at the upper left.

Magma produced lots and

lots of ore over the years and employed many local miners and

support personnel. In the end, the mine was purchased by BHP

and then shut down. The surface structures were dismantled

and sold or scrapped. The smelter was dismantled, the smoke

stacks were dynamited and the area reclaimed. My cousin Jim

was part of the reclamation and restoration effort and was on-site

when the smelter stacks were blown, see photos below.

And just like that, an era came to a close.

In addition to the still photos, Jim also captured video, see

this link for the video of the stack collapse.

A variety of Youtube videos are available on Magma including the

"definitive history" by Onofre Tafoya, one of the old

timers. See

this link for more videos.

Working at the mine was hot, dirty, dangerous, thankless work that

paid the bills. I had a number of close calls there, but was

never seriously hurt. That said, I am glad that I became an

engineer and never had to work underground again. I did

return to the mine, but as part of a tour run by a school

classmate that worked there. It was an exciting tour, but

brought back some unpleasant memories.

Back to Bill Caid's Home Page

Copyright Bill Caid 2020. All

rights reserved.